1986 CRITICS’ PICKS

SANDY BALLATORE

Laura Lasworth

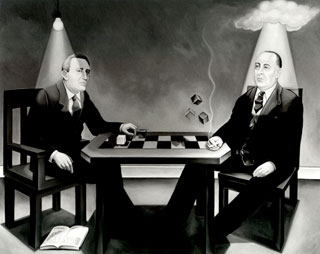

Laura Lasworth’s paintings could be described as Alice in Daliland or Pollyanna goes to the Mental Hospital. The contrast of the artist and the work is jarring: Lasworth lives and looks like a contemporary Alice who has stepped back through the looking glass, from a childhood of emotional tumult - symbolized in her paintings by distorted perspective, hot color, theatrical lighting, floating papers and figures - to an ordered reality of her own making, one in which she intellectualizes mental illness and pictorializes it in imagery that’s borderline playful.

If one seeks an example of art as a cathartic activity, Lasworth is the best I’ve seen for many years. Unlike the flood of predictable personal content unleashed by the women’s movement, specifically the horrors of housewife-ism and the destruction of self through domestic servitude, this subject matter reveals Lasworth’s direct leap into the world of the insane. She knows this world through reading and life experiences and she paints it in such a clean, tight, slick obsessive manner that one feels that she will squeeze order and logic from reality even if she must do it brushstroke by brushstroke for the rest of her life.

In the early ‘80s, her tiny timid autobiographical paintings found their way into group shows. They depicted family terrors—substance abuse, neglect, abandonment—in rooms harshly lit and eerily designed to represent states of mind, especially loneliness. Her painting style and simplification of images was, and still is, reminiscent of primary-grade textbook illustrations, the type that depict the world as a lovely place to live in.

Today, Lasworth continues to draw us into disorienting spaces in paintings that are large and assertive. We are seduced by the shiny, intense color and the clever detail - notes that we can read, for example. But the beauty that Lasworth offers is a means of digesting the horror that slowly appears. Her clinical touch tells us that neither opportunistic voyeurism nor self-pity interest her.

Lasworth has expanded from a personal focus to narratives about mental patients, capitalism, mysticism and philosophy - areas that hover at the edge of reason. In one painting, she depicts Leon Gabor, a patient in a state hospital who suffered form the delusion that he was Christ. Lasworth says, “Leon Gabor could have fooled me. He was an articulate schizophrenic who moved his psyche around like someone caught in a revolving door.” For viewers who know people who appear to function normally but reveal themselves to be mentally ill, these paintings reverberate in one’s memory like shattering glass.